Fatigue

2020

Gertrude Contemporary

Under Fatigue

Essay by Mark Feary

‘Prison offers the same sense of security to the convict as does a royal palace to a king’s guest… the masonry, the materials, the proportions and the architecture are in harmony with a moral unity which makes these dwellings indestructible so long as the social form of which they are a symbol endures.’ Jean Genet, The Thief’s Journal, 1949

Had this text been written in advance of the opening of Foster & Berean’s exhibition Fatigue, it may very well have taken a fundamentally different focus. The exhibition shares a narrative with a number of exhibitions the world over, all inaugurating the first gallery and museum presentations of 2020, many of which hastily foreshortened by the dramatic onset of the pandemic. The fact that Foster & Berean’s works draws directly upon architectural features from a number of prison and correctional facilities eerily foreshadowed the phenomenon much of the global population now finds itself in, or in the still tumultuous aftermath of, in various states or levels of governmentally ordered lockdown. Previous to the unfolding events of 2020, the term lockdown was principally used in relation to prison protocols to restrict movement in a heightened environment of potential breach or disorder. Now it is our shared global reality. Living in isolation within the confines of one’s home is no longer reserved for those serving sentence, but rather, for many, directed to live in a form of house arrest. The conditions of our respective cells invariably differ substantially, but the restrictions on our freedom of movement are similarly enforced. But while we currently hole up in isolation under broad and never before experienced governmental ordinance, for reasons of individual and collective health risk minimisation, such safety assurance cannot be guaranteed in prisons the world over, with many such facilities becoming rampant clusters of infections over recent months.

Working in collaboration since the early 2000s, Foster & Berean have focused their research and artistic output upon interconnectivities between the disciplines of art and architecture. Foster & Berean may be educated and practiced in the field of architecture, yet it is not toward the design and construction of architectural structures and buildings that their collaborative practice is oriented. Instead, their research and work is concerned with how architecture and urban design is employed to determine the behavioural conditions and possibilities of the individual, or how built structures might govern, structure or define the agency of one in a physical environment, and through this, reinforce the dominance of structural control upon the spatial and psychological potential for liberty and free movement. With a focus on interrogating how urban design and planning principles might be employed toward controlling and limiting movement and access within public environments, their work elucidates strategies for the functionality of architecture to determine what is prohibitive. Here the emphasis shifts from how architecture might serve the individual, as espoused by Le Corbusier’s suggestion that a ‘house is a machine for living in’, toward a more Orwellian reading of how the architectural environment might determine, define and surveil how individuals can live within it. The concerns of the artists are not in reverence of architectural history, exemplars of architectural vision or the enduring legacy of monumental structures to define their era. Their focus could more aptly be considered as a critique of the non-architectures that define much of the built urban environment, the seemingly non-designed buildings that deter through their foreboding presence, the structures that stringently define how they are navigated through, around or away from, and the strategies of urban planning that inhibit congregation and heighten the capacities for surveillance. Such are the architectures we do not so much see, so much as feel.

When one thinks about the architecture of prisons, correctional facilities and many other forms of permanent structures for incarceration (as opposed to architectural structures one might associate with detention centres, which frequently begin as temporary structures, then become semi-permanent until unfortunately permanent), gestures of architectural embellishment or ornamentation do not instantly spring to mind. Correctional architecture is more readily understood for the severity of industrial structuralism and surveillance capabilities. Admittedly, most would conjure a structure formed entirely through television and cinematic representation, fewer through actual visitation, and fewer again through longer obligation. The architecture of prisons and correctional facilities have always sought to impose a formidable dominance over the individual to constantly reinforce an environment of control. If there are gestures to grant any degree of understanding out of a highly controlled environment of isolation, it is through a set of highly controlled security measures.

Foster & Berean’s Fatigue takes cue from the architecture of incarceration, drawing focus and reference from a number of renowned and notorious structures as exemplars of the political and societal manifestations of the judicial and punitive mechanisms of their time. The artists have maintained their collaborative practice whilst living at distance from one another, Pat Foster in East London, and Jen Berean returning to Melbourne after almost a decade working in New York, and their interests in specific architectures reflect these settings. Each of their lived environments evidence the embedded presence of correctional facilities, and the judicial priorities that selectively populate them. The architectural structures that inform the works in Fatigue are drawn from facilities in Brooklyn, San Francisco and East London, with particular reference to the Marin County Civic Center, located in San Rafael, California, the largest public project contributed by Frank Lloyd Wright, completed in the early 1960s, and the Metropolitan Detention Center, Brooklyn (MDC Brooklyn) located in the New York neighbourhood of South Slope built in the early 1990s. The distinctive architecture of the Marin County Civic Center has inspired and featured within a number of seminal science fiction films, notably George Lucas’ first feature film THX 1138 (1971) and more recently, Andrew Niccol’s dystopic 1997 film Gattaca. It should be noted that Wright’s original design was solely for the civic administrative building, while in years following, additional buildings designed by other architects have been constructed in relation to and adjoining the 1962 building. These include the Hall of Justice building completed in 1966, and the Marin County Jail, designed by architectural firm AECOM and completed in 1994. On the evolution of the expanding campus of administrative, judicial and correctional facilities, writer Min Li Chan notes: ‘This convergence — of the governing and the governed; the free and the incarcerated; the legislative, judicial and market-driven — brings into relief the vicissitudes of civic life.’1

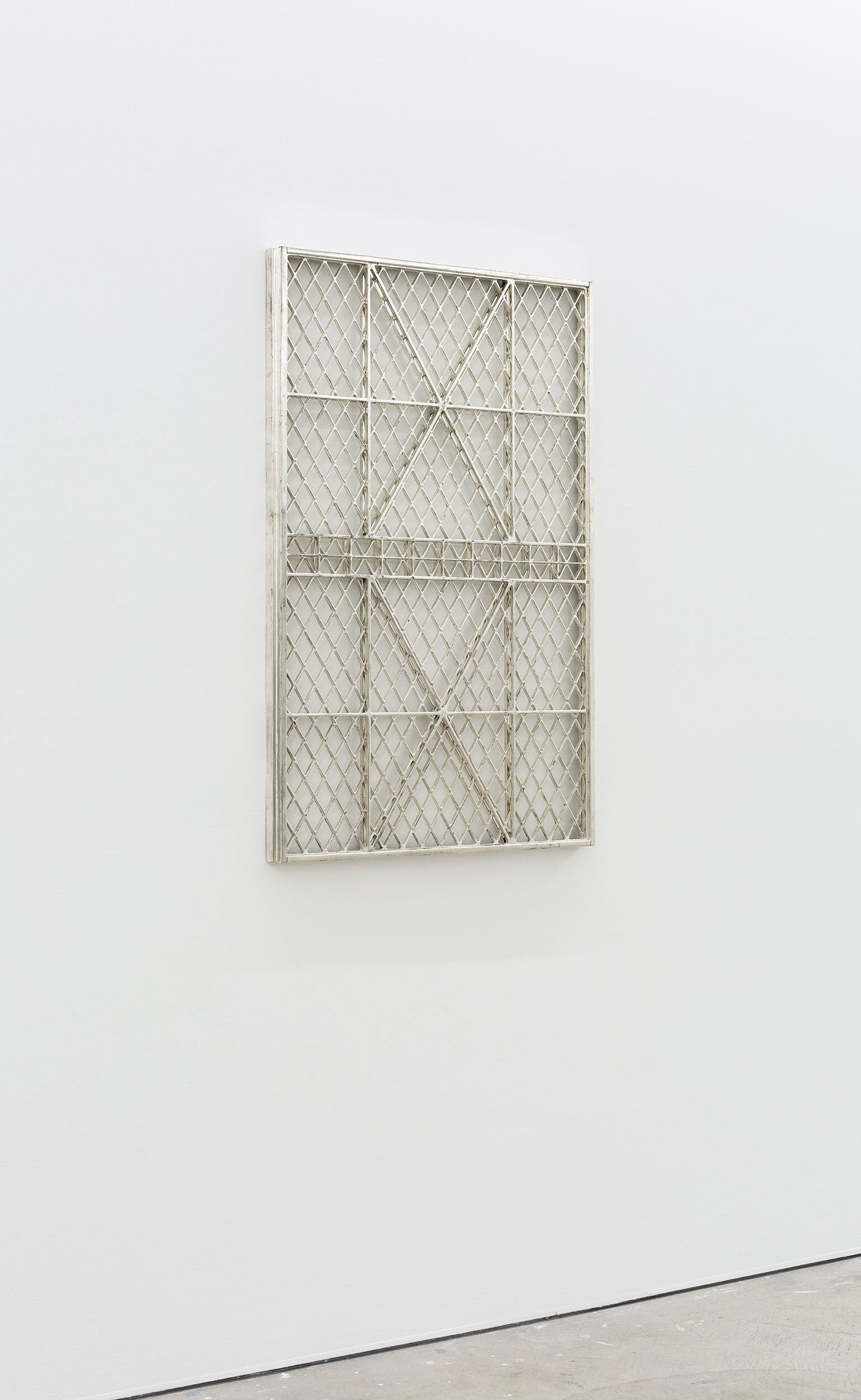

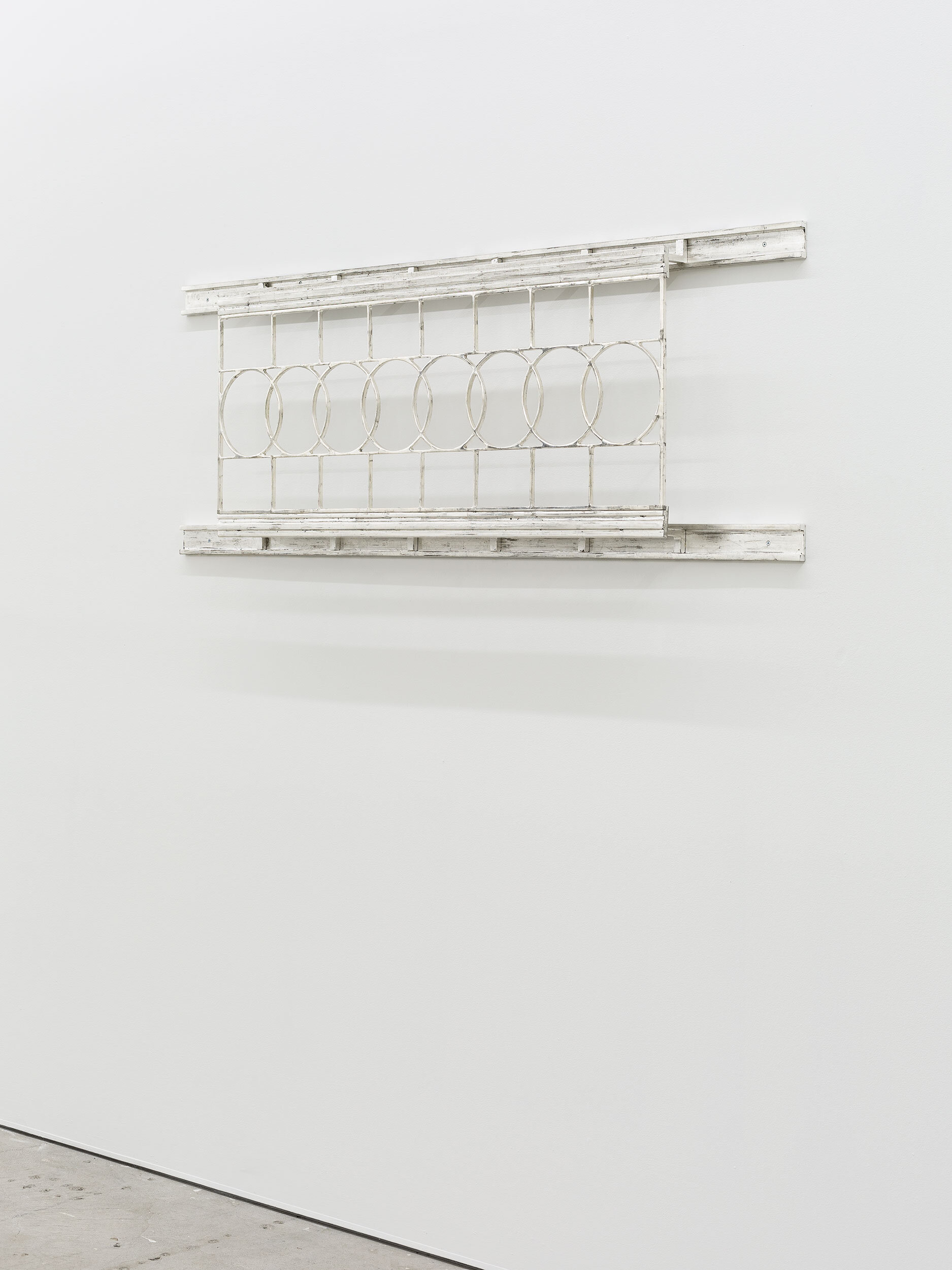

From such facilities, and in reflection of remaining and 19th and early 20th century facilities across London and their legacy as early experiments in panopticonic design, Foster & Berean focus upon extrapolating design motifs to bring to the fore, internal elements rarely seen by the public, or external elements that in part serve to conceal or obfuscate the functional purpose of the architecture. These congregated elements pay a form of tribute to the embellishments that the architects have been able to imbue within their designs, often in defiance of their clients’ (be they governmental, or more commonly over recent decades, private contractors) apparent desires for the reduction of architecture and a default position of functional austerity. As one of the costliest building types to construct, prisons and correctional facilities remain nevertheless committed to favouring punitive environmental submission, over the possibilities of employing architectural and behavioural theories toward structures more conducive toward rehabilitation.

For all of the industrially manufactured structural strength and functional objectives of the contexts from which the original grates and gates so inform the three main compositions of Fatigue, we are instead presented with is design elucidation rendered through one of the most arcane and painstaking labourious material methods fathomable. The surface areas of the works are entirely hand gilded in silver by the artists utilising an excessively laborious and now almost redundant artisanal technique. Water-gilding is a complex decorative technique involving five sequential stages that can be traced to Egypt of from at least 2300 BCE. Over many thousands of years, and across Asia, the Middle East and Europe the technique has been separately refined and employed to embellish objects or manuscripts. The medium was highly privileged in artworks with religious content or to reinforce the wealth and opulence of monarchs, with greatest prominence within the Middle Ages through to the Late Baroque. Suffice to say, water gilding is not a form of beautifying readily associated with modern correctional facilities.

The folly of the highly laboured surface treatment, deeply imbued in the concentration of its labour and artisanal nostalgia, belies the technological techniques and materials upon which the gilding is applied. Their structural bases are manufactured from an engineered wood composite, CNC routed with designs rendered through modern architectural design software. But it is from the process of the painstaking gilding that the exhibition adopts its title, Fatigue, acknowledging the toil of the processes to eventuate a finish replicating the aged appearance of steel. The hundreds of hours spent upon this ruse toward a patina that appears like the natural aging wrought upon a utilitarian material over some decades suggests an of unnecessary labour undertaken as if to pass vast tracts of time. Presented in the starkness of the white gallery space and its austere illumination, these works present as an extrapolation of and tribute to overlooked architectural ornamentation, an exercise in elaborate labour, and signifier of environments wherein the passing of time is monotonous and seemingly endless.

Fatigue can unquestionably be interpreted through the lens of isolation, or more pointedly, isolated confinement, but crucially at this time, it directs us toward the structural mechanisms for incarceration and the broader armature of the policing and judicial systems. The guilt and remorse that society demands of those individuals incarcerated toward the recognition of their divergence from the parameters of accepted societal behavioural order, are now being brought into closer scrutiny. The mechanisms of law and order that seem to voraciously target and persecute the already marginalised through a system unfairly and unduly oriented around reinforcing structural systems of power maintenance. Through this, Fatigue directs us toward a broader system of control and punishment under extreme stress.

Mark Feary, 2020

1 Min Li Chen: ‘Civic Commons: Frank Lloyd Wright and a Jail’, polis, 12 February 2012, https://www.thepolisblog.org/2012/02/civic-commons-frank-lloyd-wright-and.html